Why would we want hydrogen power?

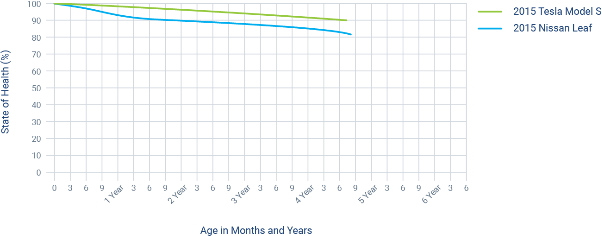

The shift away from petrol and diesel vehicles, due to the UK ban set for 2030, has driven a rapid uptake in electric vehicles (EVs). While EVs offer emissions reductions during use, several long-term challenges remain. One of the most pressing issues is battery degradation caused by repeated charging and discharging cycles. The best option is lithium-ion batteries such as those used in early Tesla models, which can withstand around 1,500 full cycles. In practice this allows vehicles to rack up 300,000 miles with around 12–15% loss in charge storage, which is more than the lifetime of most internal combustion engine (ICE) cars.

However, performance and longevity vary widely across the EV market. More affordable vehicles such as the 2015 Nissan Leaf often rely on passive air-cooled batteries, which degrade faster than the liquid cooled systems used in higher end models. As EV adoption increases globally, this raises questions about durability, cost, and waste when these vehicles reach the end of their useful life. Without effective recycling, lithium-ion batteries possess environmental risks due to toxic materials.

The emissions benefit of EVs depends strongly on how the electricity used for charging is generated. During periods of high wind and solar output, UK grid carbon intensity has fallen to around 38 g(CO₂)/MWh, compared with an average closer to 120 g(CO₂)/MWh (NESO, December 2025). When renewable output is low, charging relies more heavily on fossil generation or imports, increasing emissions, making the EVs no better than traditional petrol and diesel.

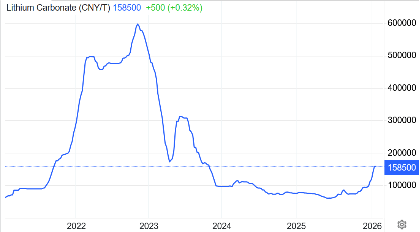

Looking further ahead to the year 3000, raw material availability becomes a serious constraint. Lithium, cobalt, and other critical minerals used in batteries are finite and geographically concentrated. Even today, mismatches between supply and demand have caused sharp price increases, most notably in 2022 (see Figure 2). If all energy systems remain heavily dependent on lithium-ion batteries for centuries, resource scarcity and geopolitical tensions could slow the transition to a lower emission global energy system.

A possible solution? - Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles

Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (HFCEVs) offer an alternative pathway. Instead of drawing electricity from the grid, these vehicles carry hydrogen, which is converted into electricity onboard through a process often described as reverse electrolysis. Hydrogen enters the fuel cell at the anode and oxygen enters at the cathode, producing electricity, heat, and water.

HFCEVs share a similar architecture to battery EVs. Electricity powers an electric motor, while a small battery stores energy from regenerative braking. Because this battery is much smaller and experiences fewer deep charge-discharge cycles, degradation is significantly reduced, potentially extending vehicle lifetimes beyond current EVs. At the point of use, the only direct emission is water vapour. If the hydrogen is produced using low-carbon electricity, lifecycle emissions can be extremely low. Despite these advantages, uptake has so far been limited.

What’s the problem then?

The main barriers to hydrogen vehicle adoption today are cost, infrastructure, and policy support. In the UK, the most accessible hydrogen passenger car is currently the Toyota Mirai, priced at over 50,000 GBP. Sales have fallen sharply in recent years, from around 65 vehicles in 2019 to almost zero in 2024 and 2025, reflecting both high upfront costs and a lack of refuelling stations.

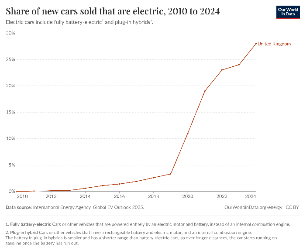

From a long-term perspective, however, these barriers may not be permanent. Investment in electric drivetrains for battery EVs is already driving down the cost of motors, power electronics, and control systems. Hydrogen vehicles use many of the same components, meaning that economies of scale and technological learning could significantly reduce costs over centuries. The fall in EV prices and increase in uptake following largescale investment provides a clear precedent (see Figure 3).

Lithium batteries Vs Hydrogen price volatility

A further driver for hydrogen adoption is resource security. As the world electrifies transport demand for lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements is expected to grow substantially. Today’s energy geopolitics are dominated by oil and gas; future tensions may centre on access to critical minerals. Countries such as the United States are already investing heavily in domestic lithium production to reduce reliance on imports, particularly from China.

Since 2022, lithium markets have experienced periods of oversupply as producers invested in anticipation of rapid EV growth, but uptake has progressed more slowly in some regions than expected. However, increased renewable deployment, grid scale battery energy storage systems (BESS), and continued EV growth are all expected to drive demand upwards again, likely to outpace supply in the long term.

Hydrogen production, by contrast, is not constrained by a single scarce mineral. Instead, it can be produced through the electrolysis of water:

2H₂O (l) → 2H₂ (g) + O₂ (g)

The key inputs are therefore water and energy. Currently, most commercial hydrogen comes from natural gas reforming, which produces carbon dioxide as a byproduct. However, when electrolysis is powered by renewable electricity, hydrogen becomes a low carbon energy carrier with potentially far greater long-term stability than oil or lithium-based systems. The rapid global expansion of renewable technologies, particularly solar photovoltaics whose costs have fallen dramatically, strengthens this case. Even in developing regions, decentralised solar combined with storage is already enabling off-grid energy systems.carbon energy carrier with potentially far greater longterm stability than oil or lithiumbased systems. The rapid global expansion of renewable technologies, particularly solar photovoltaics whose costs have fallen dramatically, strengthens this case. Even in developing regions, decentralised solar combined with storage is already enabling offgrid energy systems.

Logically, this stability supports long term government investment. In the UK, hydrogen already features prominently in future energy planning, including the NESO Future Energy Scenarios, which explore largescale hydrogen deployment across transport, industry, and power systems.term government investment. In the UK, hydrogen already features prominently in future energy planning, including the NESO Future Energy Scenarios, which explore largescale hydrogen deployment across transport, industry, and power systems.

How will we store and transport the hydrogen?

Compared with traditional fossil fuels, hydrogen contains more energy for its weight (specific energy density), but less energy for its volume (volumetric energy density). This means that, unlike petrol or diesel, it takes up a large amount of space unless it is compressed or cooled. To store useful amounts of hydrogen, it must either be compressed into high pressure tanks or cooled to extremely low temperatures so that it becomes a liquid. These remain the most common storage methods today.pressure tanks or cooled to extremely low temperatures so that it becomes a liquid.

Compressed hydrogen avoids losses from evaporation but requires strong, heavy tanks and energy intensive compressors. Liquid hydrogen takes up less space, but some of it slowly boils away and it must be kept at around −253 °C, which requires additionalenergy and specialised materials. In the future, hybrid approaches that combine cooling, compression, and new storage materials could reduce these drawbacks. Large scale storage and transport still remain as other important technical challenges to overcome. Currently there are 15 hydrogen fuel charge points around the UK, as opposed to the 73,334 electric vehicle charging points.

Reduce reuse recycle! Using the cars we already have first:

Hydrogen does not need to be limited to fuel cells. Another potential pathway is blending hydrogen with conventional fuels, such as ammonia or methane, for use in existing internal combustion engines. While this approach would give transportation a higher CO2 per km than fuel cells, it offers a modest transition strategy.

As the UK phases out new petrol and diesel vehicle sales by 2030, a key concern is the embodied carbon in manufacturing an entirely new vehicle fleet. Hydrogen fuel blends would allow existing vehicles to remain in service until the end of their useful life while significantly reducing emissions - similar to how biofuel blends are used today. Over long timescales, such transitional solutions could play an important role in reducing emissions while hydrogen infrastructure and vehicle technologies mature

With current hydrogen production methods, a hydrogen powered car would increase overall energy consumption compared to a diesel-powered car. Biodiesel alternatives such as HVO (made from vegetable oil) end up with lower energy consumption and emission values. However, with established green hydrogen infrastructure (production, distribution and storage), there is potential for the higher energy consumption to be negated.

Looking towards the year 3000:

By the year 3000, transport systems will need to be not only low carbon, but also resilient to resource scarcity and geopolitical instability. Hydrogen, particularly when produced using renewable energy, offers a pathway that is less dependent on finite minerals and more adaptable to a fully decarbonised global energy system. While significant technical and economic challenges remain, hydrogen’s role as a long-term energy carrier is essential for a sustainable transport future in the UK and beyond.carbon, but also resilient to resource scarcity and geopolitical instability.

What might it take to get there?

The key points to get hydrogen vehicles on the road will be investment into renewable powered electrolysis sites, transportation and storage systems for the hydrogen, fuelling points for hydrogen vehicles, and subsidies on hydrogen powered vehicles. The most difficult one will likely be cutting costs for current HFCEVs from 50,000 GBP and above to closer to the current EV price points, however this is possible much sooner than the year 3000. In 2015 the cheapest electric car price was 30,000 GBP for the Nissan leaf, and now there are options at 12,000 GBP for the Dacia Spring. Since all petrol and diesel cars are scheduled to be banned from sale after 2030 in the UK, there is serious potential for diversification in what car companies sell - from just BEVs to focusing on other options such as HFCEVs.

https://www.geotab.com/uk/blog/ev-battery-health/

https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/lithium

How many TOYOTA MIRAI were made & sold in the UK

Lithium Has Become a National Security Priority for the United States | OilPrice.com

Hydrogen Cars in the UK 2025: The Complete Buyer's Guide to Fuel Cell Vehicles - AutoHit

Future Energy Scenarios (FES) | National Energy System Operator

https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/17/18/4728

Electric vehicle public charging infrastructure statistics: January 2025 - GOV.UK