The Energy Transition

You may have heard the phrase “The British love to queue,” but are we now letting our electricity queue up as well? In recent years, protests and activist campaigns, from climate marches to groups like Just Stop Oil, have sought to highlight the urgency of the climate crisis and push policymakers toward action. The importance of keeping global warming within 1.5 °C was reaffirmed at COP26 in the Glasgow Climate Pact, signed by more than 200 countries. The pact called for an accelerated “phase down” of coal and the reduction of fossil fuel subsidies, pointing toward a rapid shift to renewable energy.

On the surface, these renewables seem like the magic fix. We imagine a seamless swap: more solar panels, more wind turbines, and fossil fuels fade quietly out of use. We continue to live much as we do now, plug in our appliances, flick on lights, drive to work in an electric car instead of a petrol one, and the system around us will simply rearrange itself.

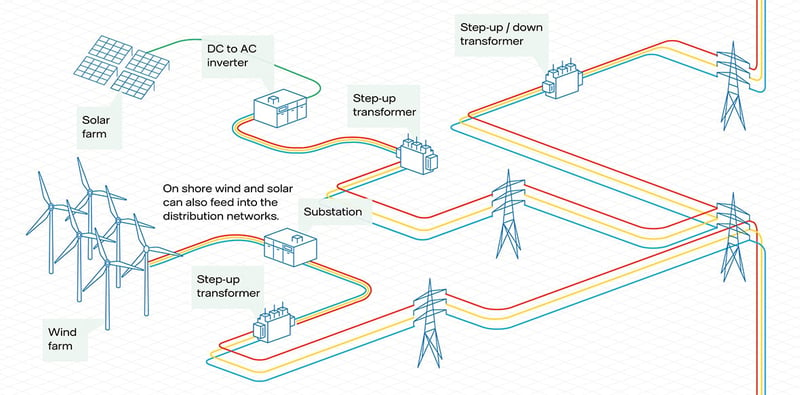

But the reality is far more complex. The UK’s reliable electricity grid, where blackouts are rare and every socket reliably delivers 230 V at 50 Hz, rests on a vast network of generation plants, substations, and transmission and distribution lines built over decades. Connecting new generation into this system is not the equivalent of plugging into a wall socket; it requires careful planning, sufficient physical capacity, and upgrades that may take years. These interconnected, reliable systems come at a cost, and as we invest in new sources of electricity, both complexity and price pressures tend to rise, at least initially.

The Cost of New Connections

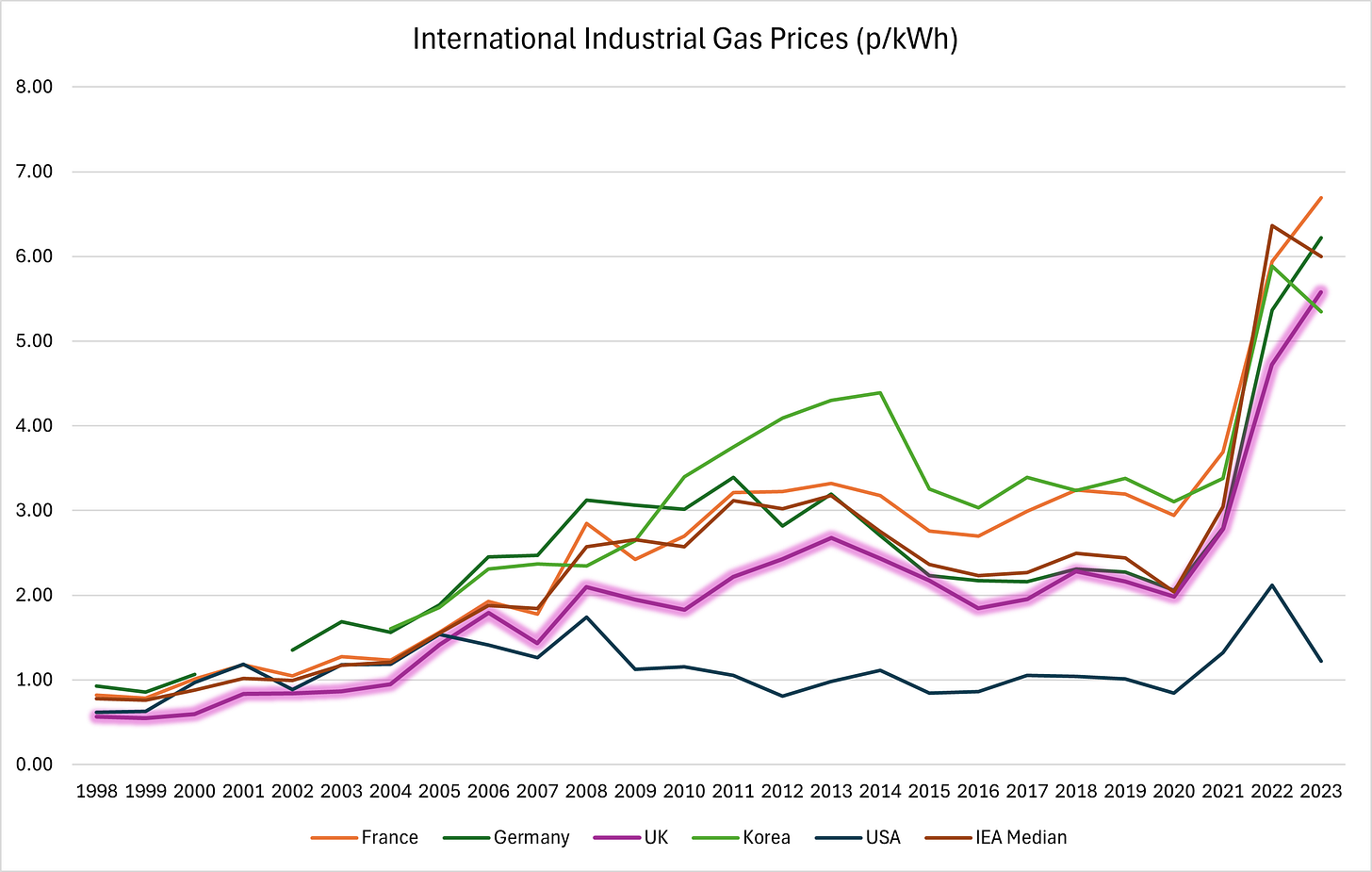

The UK already faces one of the highest electricity prices in the developed world. Industrial and household rates remain significantly above those of comparable nations. According to recent government analysis, UK domestic electricity prices were 45% above the median of the 28 countries assessed by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2024 while gas prices sat below the median, suggesting structural issues in the electricity system are contributing to this cost gap.

Affordability is not simply a matter of statistics; it has consequences. Households on fixed incomes, pensioners, and benefit recipients, who often are living in older, energy inefficient homes, must devote an ever-larger share of limited income to energy bills, pushing many into fuel poverty. A household is considered fuel-poor when it must spend a disproportionate share of income on energy and still cannot maintain an adequate heating regime. Poor insulation, cold homes and the high cost of retrofitting only exacerbate the problem. Energy costs are not just a bill; they are a social pressure that shapes quality of life. As new infrastructure is built and connected, these factors must be considered. Although you do not immediately see the cost of a new solar farm in your monthly bill, the investment needed to expand, reinforce and operate the network ultimately flows through to the end consumer.

How Are the Connections Queueing?

Overlaying this challenge is another, less visible one: the queue for grid connections. The grid is not a single socket waiting for more plugs. It is a system in which connection dates depend on plans, capacity, and local network limits. That “when” has become a national bottleneck. According to the Clean Power 2030 Action Plan, around 739 GW of generation and storage capacity is currently waiting to connect to the network - far more than the UK will need and that can feasibly be built by 2030. Many of these projects are speculative, lacking planning permission, funding, or land rights. Even so, they occupy crucial positions in a first-come, first-served queue, delaying more mature developments.

Developers with land rights, planning consent and serious investors behind them have in some cases been given energisation dates in the late 2030s. Frustratingly, the projects needed to decarbonise our electricity system are stuck in line behind others that may never be built.

Recognising the scale of this problem, the government and the National Energy System Operator (NESO) have initiated a major overhaul of the connections process. The Clean Power 2030 Action Plan describes an “over-subscribed” system where speculative entries have hindered network planning. NESO’s reform effort spans three phases: demonstrating the need for change, designing the solution, and finally specifying the detailed framework required to implement it,.

The Connections Queue Reform

The core of the reform is simple: shifting from first-come, first-served to first-ready, first-connected. Under this system, projects showing genuine readiness - including planning consent, secured land, viable designs, and evidence of alignment with Clean Power 2030’s capacity ranges - are placed into Gate 2, getting priority connection offers. Less mature projects fall into Gate 1, receiving indicative, not firm, dates until they progress.

The potential impact is substantial. Industry analysis and government modelling suggest that applying readiness and alignment criteria could shrink the queue by more than 60%, identifying about 360 GW of projects that lack necessary maturity and a further 122 GW that do not align with clean-power priorities. A shorter queue not only accelerates timelines for viable projects but also allows NESO to plan network reinforcements around genuine development intent rather than speculation. The Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) expect the new fast-track system to be operating this year, with earlier connection dates for ready projects starting in 2026.

Still, a key question remains: will this work? And can the queue ever truly disappear? The answer is that the queue will never vanish entirely, nor should it. Any finite network needs a process for allocating scarce capacity, but a queue measured in months rather than years is achievable. The challenge is execution. Criteria alone are not enough; they must be strictly enforced. If developers can enter early, speculation will re-emerge. A strict filtering system is essential.

The Economics of the Queue

This is not just an engineering concern; it is also financial. The UK depends heavily on private capital to deliver its decarbonisation goals. Yet capital must flow toward buildable projects, not placeholders. The World Energy Trilemma Report 2024 warns that failing to balance energy security, affordability and sustainability can create systemic tensions in investment flows, heightening volatility and risk. For a country already facing affordability issues, weak project screening carries real dangers. If speculative projects use up investment and then fail to progress, the sector risks developing a bubble - inflated expectations without delivery, followed by disruption when projects stall.

To avoid this, investors must trust that connection priority signals readiness, not mere enthusiasm. Rejection of infeasible or misaligned projects is essential. Only by channelling capital toward feasible developments can the UK attract sustained investment without increasing costs. For a system already grappling with high electricity prices and fuel poverty, maintaining that balance is key.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the reform aligns the connections system with the UK’s strategic objectives. The Clean Power 2030 Action Plan defines the capacity ranges needed for a secure, low-carbon grid, and these ranges now feed directly into how connections are prioritised. The aim is not merely to shorten the queue but to make it smarter, a queue that reflects real projects aligned with national need.

The issue, then, is not the existence of a queue, but its previous inefficiency, its misalignment with net-zero goals, and the uncertainty it imposed on investors. By shifting to a readiness-based system and clearing blockages, the UK has a path to restoring confidence and speed up the projects needed for affordable, clean power.

So even though the British may still love a good queue, if the connections reform works as intended, our renewable energy might finally get to skip ahead.

Soruces

[1] House of Commons Library (2021) What were the outcomes of COP26?

[2] DESNZ, Energy Prices: International Comparisons – Domestic Electricity Prices in the IEA, 2025.

[3] House of Commons Library, Fuel Poverty in the UK, 2025.

[4] National Energy Action (NEA), Energy Crisis – What is Fuel Poverty?, 2025.

[5] NESO, Connections Reform – Design Documents & Methodologies (Phase 2 & Phase 3), 2024–2025.

[6] NESO, Evidence Submission Handbook for Connections Reform, 2025.

[7] S&P Global Commodity Insights, UK Cuts Grid Queue by 64% and Slashes Wait Times, 2025.

[8] World Energy Council, World Energy Trilemma Report 2024.

[9] UK Government, Clean Power 2030 Action Plan: A New Era of Clean Electricity, 2024.

[10] Ofgem, Clean Power 2030: Proposed New Fast-Track Grid Connections System, Press Release, 2025.

Pictures sources:

Figure 1 How the National Grid works - Vattenfall IDNO - Independent Distribution Network Operator

Figure 2 We're number one... in unaffordable electricity — Institute of Economic Affairs

Image 3 https://www.pexels.com/photo/coins-on-white-surface-12955794/