Curtailment: The Hidden Factor Driving Up Energy Prices and Stalling the UK’s Energy Transition

The Problem

“In 2024 the UK paid over £393 million in direct costs to discard 8.3 TWh of wind energy, the bulk of which stemmed from Scottish wind farms.”

When thinking about the current issues facing the UK energy industry, the problem of simply having too much renewable capacity may not immediately spring to mind as a major issue. Yet, it has become one of the most significant challenges facing the country’s decarbonisation goals. This phenomenon is known as curtailment, which is when energy regulators deliberately reduce, or even completely stop, a generator on a temporary basis. When this happens, the grid is then forced to pay generators to reduce their output, with those costs ultimately reflected in electricity prices for consumers.

While we often (rightly) think of renewables - specifically wind power in this context - as essential for decarbonising our power production, poor grid planning has turned curtailment into a growing environmental, economic and public perception problem. This article argues that the UK, and Scotland in particular, has overinvested in renewable generation while underinvesting in infrastructure (energy storage and transmission). The result is a short-termist blunder that wastes green power and contributes to disproportionately high energy bills across the country. In short, successive UK and devolved governments have successively greenlit plans for large scale, high-megawatt wind farms, the benefits of which have been minimal for the average consumer.

Regional Imbalance

Looking at data published by the Scottish government in 2022, this was the first year that Scotland produced more electricity from renewables than it was able to use domestically, creating a vast energy surplus that it is unable to export south to higher population areas.

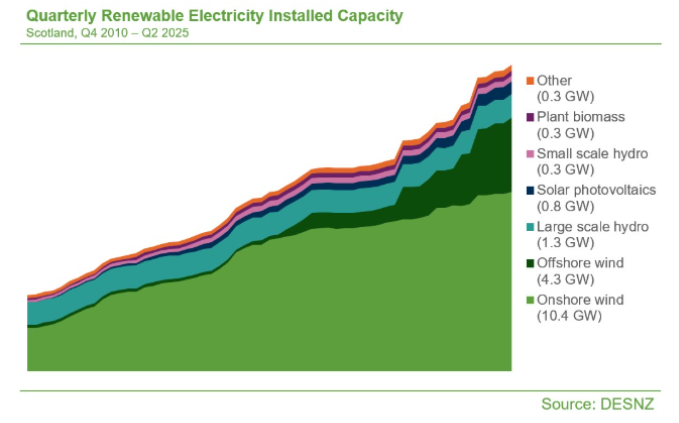

Yet, despite this persistent imbalance, the pipeline for new renewables projects remains extensive. Data shows that as of Q2 2025, there are still 34 gigawatts (GW) of wind energy both offshore and onshore in the current pipeline for construction in Scotland alone.

This situation is partly a consequence of devolution, which gave Scotland considerable autonomy to approve and promote energy projects. Throughout the 2010s and 2020s, the SNP government pursued an aggressive expansion of renewable technologies (see Figure. 1). These policies were politically popular and highly visible on the international stage (e.g. during COP26 held in Glasgow), but were not matched by proportional transmission investment. The result is a severe regional imbalance: wind-rich areas in Scotland and parts of northern England now have a renewable energy surplus they can’t export. This has been compounded by the ageing UK grid, much of which was designed for centralised fossil fuel production rather than today’s variable, decentralised renewables.

What was for quite some time being hailed as a success story of the Scottish government, is now transpiring as a complex logistical problem for the UK as a whole.

The Broader UK Problem

The problem of curtailment within the grid is symptomatic of a much wider issue for the UK. The national grid was originally designed and built to sustain legacy fossil-fuel generation, and the rapid expansion of new, poorly interconnected solar and wind developments has not been matched by equivalent transmission upgrades.

In many ways, this reflects a broader trend of “kicking the can down the road” policymaking, as successive governments have sought short-term wins on climate statistics. Impressive headlines - such as the UK no longer using coal in electricity generation since 2024 - mask the deeper infrastructure problems that remain. However as bad as coal is as a pollutant, its place within the grid as a reliable, easily dispatchable source of power should not be understated.

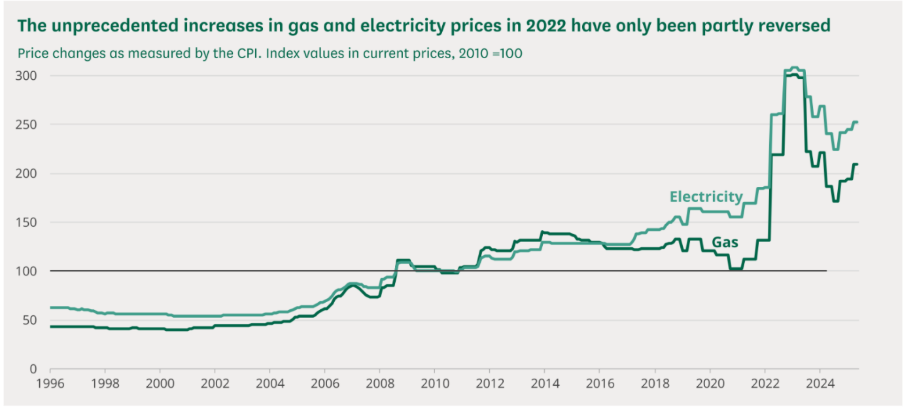

This highlights the underlying dilemma of the green transition: while the shift to renewables is essential on a global emissions scale, particularly for historically industrialised nations like the UK, it should not come at the expense of domestic energy security or affordability. British consumers are now paying the price for a system that prioritised symbolic progress over operational stability, with costs soaring over the last 10 years (see Figure. 2).

Although the war in Ukraine undoubtedly contributed to recent price volatility, the root cause of the UK’s energy instability lies in a curtailed, inefficient grid system that remains ill-suited to the scale and variability of its renewable generation.

Global pattern

However, it would be remiss not to acknowledge that this curtailment anomaly is far from unique to the UK. Similar trends have appeared across the world, most notably in large, low-population regions such as Texas in the United States, where renewable generation capacity has rapidly outpaced transmission infrastructure. In these areas, vast amounts of wind power are routinely wasted simply because there is nowhere for the energy to go.

Fundamentally, our perception of energy transmission is flawed. Electricity is not a conventional commodity- it is generated, transported, and consumed almost instantaneously. Unlike oil or gas, it cannot be stored or traded in bulk without extensive supporting infrastructure. When governments such as Scotland’s greenwash their policies by focusing solely on expanding renewable capacity, they overlook this fundamental truth: energy is not just about production, but about delivery.

If curtailment is the growing pain of renewable adoption, then coordination and storage are its cure.

Paths forward

Looking ahead, there are several routes that both governments and private companies can take to alleviate and eventually rectify curtailment as an ongoing issue.

The most direct solution is upgrading the grid through large-scale transmission projects capable of handling higher voltages. This would allow Scotland and the north of England to connect more efficiently to demand centres further south. However, while such upgrades are effective, they are also vastly expensive and slow to deliver.

Another approach is to improve grid flexibility by expanding battery storage networks across the country. Similarly, increasing the share of low-carbon, non-variable generation could help provide reliable baseload power to complement renewables. Encouraging the development of microgrids would also reduce strain on national infrastructure by enabling communities to generate and manage energy locally.

Yet each of these solutions faces economic and logistical barriers. The financial models that supported the rapid, low-cost construction of the grid in the 20th century no longer exist. Overcoming this will require deliberate, coordinated action from governments, low-carbon technology companies, and grid operators such as the National Energy System Operator (NESO).

Closing reflections

The problem of curtailment is deeply entrenched within the UK’s energy system, and it will not be solved quickly. Yet the benefits of addressing it would be transformative: energy prices would stabilise, green generation would no longer go to waste, and the grid itself would become far more efficient. Fixing the grid may not be headline grabbing, but it is the basis for an energy transition truly rooted in efficient, lasting change.

Sources

Picture sources:

https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-wind-turbines-lot-1292464/

FIG 1 - https://www.gov.scot/publications/energy-statistics-for-scotland-q2-2025/pages/renewable-electricity-capacity/

Source – Energy Trends table 6.1: Renewable electricity capacity and generation

FIG 2 - https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9491/