Current energy trends

In an age of rapid technological advancement and changes to how we live our lives, we are reliant on more and more energy. In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has cemented itself in almost every corner of our lives with chatbots everywhere - even your fridge has the ability to ‘think’. This current increase in demand for energy is not sustainable without causing catastrophic effects to the planet, as is already the case. But the world is making progress, pivoting away from harmful fossil fuels towards green and cleaner energies such as wind, solar, nuclear fission etc. Hopefully, we will reach a point where fossil fuels are a distant, unsavoury memory and we live in a world powered by turbines, solar panels and perhaps the splitting and fusing of atoms.

Peering through the looking glass to the year 3000

Even in the year 2026, your day is filled with technologies which are all hungry for energy, and forever in a state of growth. What will be the norm in almost 1,000 years, is unimaginable to us now. However, we can take an optimistic stab in the dark and hope that humans will be prospering with incredible facilities and technologies. Perhaps civilisation will have advanced into space and declared new homes throughout our solar system and beyond? What can be said with certainty is that our progress will be dependent on our source of energy, because it is not sustainable to continue with fossil fuels which will quickly deplete, leaving us with the lasting reminder of our mistakes in the form of a flooded, warm world.

Vast amounts of energy will likely be needed constantly, and the energy grid will need a strong backbone to push humanity forwards. That backbone will be fusion.

Nuclear fusion, an energy gold-mine

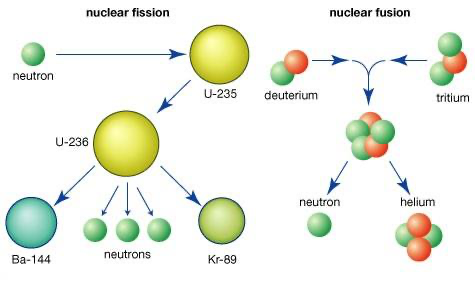

Nuclear fusion may sound intimidating and dangerous to those who do not yet understand it. The word ‘nuclear’ strikes fear to many: war, disaster and death. While fission, which is used in nuclear power stations, may bring these threats if mishandled, fusion will not. There is no danger of run-away reactions, or out of control surprises, due to the fundamental truths of nuclear fusion.

You may have heard of this physics phenomenon, or you may have seen it in the news, but not conceptualised what it truly means. I’ll start by saying that fusion is what happens at the heart of every star in our sky. There is the misnomer that the Sun is ‘burning’ away and is a big ball of fire, but that is an oversimplification and just plain wrong. The Sun is a ball of gas with immense mass and gravitational pull towards its centre. Because there are such incredible pressures and temperatures at the centre, the simple hydrogen nuclei can ‘fuse’ to produce helium nuclei, which is accompanied with energy. This energy stops the gravitational strength of the Sun from compressing and collapsing and ensures an equilibrium size of our star. The idea that we can harness the power of stars in laboratories on Earth is almost laughable but is now actually a truth.

Fusion is exceptionally safe because its operation relies strictly on achieving high pressure and temperature. If we intend to stop the fusion reactions, reducing these factors immediately halts energy production.

Fusion generates significantly more energy per kilogram of fuel than any current energy source: four times more than nuclear fission and nearly four million times more than coal or fossil fuels.

There is also an abundance of the fuel used for typical fusion, that being Deuterium and Tritium which are both isotopes of hydrogen. Deuterium can be found via basic sea water; Tritium is a little trickier as it must be produced via Lithium being ‘bred’ within a reactor.But all in all, the energy production from fusion is so energy dense, that the scarcity of fuel is not a near concern. In theory, fusion could provide energy endlessly for civilisation, whilst still producing no harmful byproducts in the process. It could allow for our planet and community to flourish and advance in a cleaner world.

What actually is fusion and how is it done

As touched on previously, fusion is the process where two ‘light’ nuclei get so close to each other that they are able to merge into one ‘heavier’ nucleus. Nuclei are always positively charged due to the presence of positive protons, but a little thing to remember is that charges of the same sign repel. This becomes quite a problem when you’re trying to push two positive things together which really don’t want to be there. The solution to overcoming this electrostatic force is simple really, it's just executing it that causes issues. High pressures and high temperatures are needed to give nuclei enough energy to be close enough to one another so that another force, the attractive Strong Force, takes over and causes the merging of the two.

So, now you know what fusion is, but what are the b=number of ways in which it is produced?

It comes down to the fact that the sum of sub-atomic particles’ (protons and neutrons) mass does not equal the mass of the atom which the particles form. In fact, it’s a little less. This ‘mass defect’ is different for every element, and so if the right two elements’ nuclei are used to produce a single new nucleus, then the mass defect will be greater than the initial two mass defects. This ‘lost mass’ can’t just disappear and leave us with nothing, as that would break conservation laws. Instead, due to Einstein’s useful E = mc^2 equation,where E is energy, m is mass, and c is the speed of light, the missing mass is converted into energy, which is then released. This is the true glory of fusion.

So, if the system we set up is good, then we can get more energy out than we put in, which puts us in a nice spot.

The way we implement fusion is the actual tricky bit - the pure physics has been understood since the 1930s. We currently have three main ways which can produce fusion, each utilising a different area of physics: magnets, lasers, gravity. Gravity is the most effective,but unfortunately an unattainable method on Earth (I will leave it to you to figure out why that is).

The leading method for fusion, is currently Magnetic Confinement Fusion (MCF) which has much more depth than we can touch on here, so I will generalise. Essentially, very strong magnetic fields hold and contain plasma which contains the reactants. Plasma is just a fancy word for charged slush, where the electrons which usually accompany the nucleus, have separated. The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) is currently being built in France and will be a massive international fusion research project site. It is already home of the largest pulsed electromagnet, which can lift 100,000,000kg off the ground. Magnets and floating confinements are vital, as the plasma must be kept at temperatures of around 100,000,000 °C so it does not interact with the confinement walls and cause major damage requiring frequent repair and replacement.

Inertial confinement fusion (ICF), or lasers, are another favoured way. The National Ignition Facility (NIF) in the United States, aims to produce sustainable fusion via the firing of 192 lasers towards a central pellet which houses a grain sized collection of atoms. The pellet will be bombarded with photons until it explodes which produces a strong inward force on the atoms which allows for fusion.

You may notice that ICF produces humungous pressure, far greater than MCF methods are capable of. Also, the heated plasma used in the MCF reaches greater temperatures than ICF. Previously it was mentioned that fusion requires high pressure and temperature. By drawing a couple conclusions, we can see that one can compensate for a lack of the other. This is the basis of the Lawson Criterion which states that for fusion to be achieved, the triple product of confinement time, fuel density (pressure), and temperature must exceed a threshold. Different methods to fusion can compensate for a lack of one of these factors by maximising the others.

It may come as a surprise that the density of the plasma used in many MCF reactors is much lower than even the air we breathe, as there is a huge lack of pressure needed. However, the temperature and confinement times are much higher than other methods which require greater pressures (such as ICF). ICF’s weakest factor is its confinement time, which is less than 1 nanosecond, but the pressure caused by the inwards reaction force from the explosion of the pellet housing the atoms, is so enormous that fusion can still be achieved.

How far off are we and what to do in the meantime?

The year 3000 is quite a way off, so let’s first look a little closer to where we are now. Many scientists do not believe fusion will be first truly established until the 2040s. This decade makrets the target for the prototype powerplant STEP to be operational, but still primarily for research benefits. Commercialisation of fusion is even further from us, which is why it is important in the meantime to continue investing and building a clean energy grid of renewables and nuclear fission. ‘Holding off in wait for fusion’ is not an option.

Various perspectives about this topic are spread online and by influential figures. Within the last year the US Energy Secretary Chris Wright stated that “The technology [commercial fusion], it’ll be on the electric grid, you know, in eight to 15 years” and has repeatedly implied that there is no need to decarbonise because future fusion prospects are enough. This ‘optimistic’ view differs from what many scientists and environmentalists believe.

Whilst I personally think fusion will be the backbone of future energy, I don’t believe that a future energy grid should ever be centred around a single producer or method, even fusion. Having a diverse energy landscape facilitates a more resilient energy grid, which is vital to be protect against unforeseen issues such as a lack of fuel material, or required downtime of powerplants. Renewables however, will always have a place as it may not always be cost effective to build or install a fusion plant in remote areas etc.

Cover Image: UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering licensed under CC by 2.0

1. https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-is-nuclear-fusion

- Discussion with Physics PhD candidate of the University of Birmingham, Rebecca Sherwin