There’s a peculiar British tradition of being brilliant at inventing things and then spectacularly rubbish at actually building them. We invented the jet engine, then let Boeing dominate commercial aviation. We created the World Wide Web, then watched Silicon Valley turn it into a trillion pound industry. And don’t even get me started on how we invented the train and now can’t seem to build a railway line from London to Birmingham without it becoming a national embarrassment.

So, when Rolls Royce rocks up claiming they’ve cracked the code on nuclear power, the thing we’ve been catastrophically failing at for decades, you’d be forgiven for being sceptical. Hinkley Point C is running about 10 billion GBP over budget and years behind schedule. Sizewell C is stuck in financing limbo. Meanwhile, the French are having their own nuclear nightmare with their EPRs (European Pressurised Reactors), and the Americans haven’t finished a new nuclear plant since the 1990s without it turning into an expensive disaster.

But here’s the thing, Rolls Royce might actually be onto something. Not because they’ve invented some revolutionary new nuclear technology (they haven’t), but because they’ve nicked a playbook from an entirely different industry. What they’re trying to do to nuclear power is what Henry Ford did to cars, what Apple did to phones, and what IKEA did to furniture. They want to build nuclear reactors in a factory.

The Nuclear Problem Nobody Wants to Talk About:

Let’s be honest about where we are. The UK has set these wildly ambitious climate targets of net zero by 2050, clean power by 2030, and nuclear is supposed to be a massive part of that. It’s the only low carbon power source that works when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining, which in the UK, let’s face it, is quite often. We need it.

But we’re absolutely terrible at building it. Hinkley Point C was supposed to cost 18 billion GBP when we agreed to it in 2016. It’s now looking more like 31-35 billion GBP and will not be done until 2031 at the earliest. That’s one plant. ONE. And it’s taken us the better part of a decade to not finish it.

The problem isn’t that nuclear is inherently impossible. The French built 58 reactors in about 15 years back in the 70s and 80s. The problem is how we’re building them. Every reactor is essentially a bespoke construction project. It’s like building a cathedral where everything’s custom, everything’s on site, everything takes forever, and everything costs a fortune. You’ve got thousands of workers in muddy fields in Somerset welding together massive steel structures, pouring concrete, installing miles of piping, all while trying to meet the most stringent safety standards known to humankind.

Of course it’s going to be expensive. Of course it’s going to take ages. Of course something’s going to go wrong.

Enter Rolls Royce and the Factory Floor:

This is where Rolls Royce’s small modular reactor (SMR) strategy gets interesting, because they’ve looked at this mess and said, “what if we just… didn’t do it like that?”

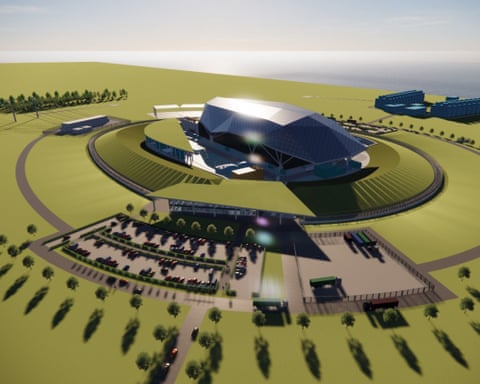

Their pitch is deceptively simple. Instead of building massive, one-of-a-kind reactors on site, they plan to build smaller reactors in a factory. Properly smaller, we’re talking 470 megawatts instead of Hinkley’s 3200 megawatts. But, here’s the clever bit, because they’re smaller, you can manufacture the components in a controlled factory environment, truck them to site, and bolt them together like a very big and very expensive LEGO!

Think about how Tesla builds cars. They’re not hand crafting each Model 3 from scratch in someone’s garage. They’ve got massive factories with robots and production lines churning our identical vehicles. The first model 3 off the line was expensive and took ages to build properly. But, the 10,000th? Much cheaper, much faster, because you’ve ironed out all the problems.

That’s what Rolls Royce is betting on. Build the first SMR, learn from all the mistakes, then the second one’s easier. The third one’s easier still. By the time you’re building the 10th, you’ve got teams of workers who have done this nine times before. You’ve got suppliers who know exactly what you need. You’ve got a fully operating supply chain that actually works. You’re not reinventing the nuclear wheel every single time.

Why Might this Actually Work?

There are a few reasons to think this isn’t just more British optimism (which, let’s be clear, has led us astray before).

Firstly, Rolls Royce actually knows how to manufacture complicated things at scale. They’ve been building jet engines for decades, which are incredibly complex pieces of kit that have to work perfectly in extreme conditions and literally cannot fail. Building a small reactor in a factory isn’t the same as building a jet engine, obviously, but it shows they understand precision manufacturing, quality control, and safety certification.

Not only that, but the UK government is also backing this. Great British Nuclear has assured SMRs are part of the plan and Rolls Royce has secured substantial funding. There’s political will behind it, which matters when you’re trying to do something ambitious. Ed Miliband seems to have figured out that if we want clean power by 2030, we need something that doesn’t take 15 years to build.

Moreover, the most important factor here is that the economics might finally work. Traditional nuclear is eye-wateringly expensive upfront, demanding tens of billions before you generate a single kilowatt. With SMRs, each unit costs 2-3 billion GBP. Still a lot, but investors can stomach that. You can build one, prove it works, then build another. You’re not betting the entire farm on one massive project that might go wrong.

Why this Might not Work:

Right, now for the cold water.

We’ve been talking about small modular reactors for decades. The concept isn’t new. What’s different this time? Rolls Royce will tell you it's the factory-built approach and their manufacturing expertise, but we’ve heard optimistic promises about nuclear before. Remember when Hinkley was supposed to cost 18 billion GBP and be completed by 2025?

The regulatory pathway is still very much a nightmare. Yes, Rolls Royce has submitted their design for approval, but getting a nuclear reactor design certified in the UK takes years! The generic design assessment process is thorough (which is good - we don't want unsafe reactors), but it’s also slow. Even if the design gets approved, building the first one is still going to take longer and cost more than anyone expects. It always does.

There’s also the small matter that nobody’s actually built one of these things yet. Not at commercial scale, anyway. Russia’s got a couple of small floating reactors, but they’re not that great, let's be honest. The Americans have been working on SMR designs for years with very limited success. China’s building some, but again, different regulatory environment, different approach. Rolls Royce is essentially saying “hey guys trust us, we’ve figured out something nobody else has managed to do at scale.” That’s a big, big ask.

And then there’s the British building problem. We’re not just bad at building nuclear, but rather we’re bad at building infrastructure in general. HS2 is a shambles. Crossrail was years late. Heathrow’s third runway has been under discussion since the 1970s. There’s a real question of whether our problem is with nuclear specifically or with delivering large, complex infrastructure projects in general. If it's the latter, SMRs aren’t going to save us.

The iPhone Analogy (and why it matters):

Here’s why I come back to the iPhone comparison. When Apple launched the first iPhone in 2007, Nokia was the dominant phone manufacturer. Nokia’s approach was to build loads of different models for different markets - cheap phones, business phones, camera phones, you name it. Apple did the opposite. They built one phone, in massive volume, and iterated on the design.

The first iPhone was expensive and had limitations. But by the iPhone 4, they had figured out the manufacturing process, the supply chain, and the ecosystem. They were churning out millions of identical devices, each one better and cheaper to make than the last. That’s the power of the factory model: you learn, you improve, and you scale.

Rolls Royce is trying to do the same thing. Don’t build multiple different reactor designs like the French did in the 70s. Build one design, perfect it, then build it again and again. Get really, really good at building that one thing.

Of course, there’s a counter argument, and that is phones are consumer electronics, nuclear reactors are safety critical infrastructure with lifetimes spanning over 60 years. Fair point. You can’t just push out a software update if something goes wrong with a reactor (although that would be very cool). But the principle of learning by doing and manufacturing at scale still applies.

What this Means for the UK Energy Policy:

If Rolls Royce pulls this off (and that is still a big IF) then it changes the game completely. We’d have exportable domestic nuclear technology (finally, something to sell to the world that isn’t financial services). We’d have a pathway to meeting our climate targets not disproportionately reliant on wind. And we’d have a solution to the intermittency problem that doesn’t require gargantuan amounts of battery storage.

The plan is to have the first SMR operational by the early 2030s. They want to build a fleet of them across the UK, and former coal plant sites are ideal because they’re already connected to the grid. If they can deliver on cost and schedule (big IFs), suddenly nuclear becomes viable again.

But here’s the thing that sort of bothers me, which is why we’ve been here before. We’ve had promising British technologies that were going to revolutionise energy. We invented carbon capture and storage tech, then failed to develop it while the Norwegians built actual facilities. We were world leaders in offshore wind, and still are, but we let Vestas and Siemens build the turbines while we just stick them in the sea.

The question isn’t whether Rolls Royce can design a good small modular reactor. The question is whether Britain can actually build the them, consistently, on budget, and at a scale. That requires not just good engineering but political will, regulatory efficiency, supply chain development, workforce training and a willingness to learn from mistakes without giving up.

What my Verdict is (sort of):

Look, I want to be optimistic. I love being optimistic. Rolls Royce’s SMR programme is probably the most credible shot we’ve had at a nuclear revival in decades. The factory-built approach makes sense. The company has the right expertise. The government likes it. The economics might actually work.

But I've also seen enough British infrastructure projects to know that hope is not a strategy. We’re amazing at the vision thing, and we can pitch, we can design, we can innovate. We’re less amazing at the boring, hard work of delivering. Building the first SMR on time and on a budget would be genuinely revolutionary. Building a fleet of them? That would require a level of execution we have not shown in decades.

So, here’s my prediction: Rolls Royce will get the design approved. They’ll build the first SMR, and it’ll be late and over budget but will eventually work. The real test comes with units two through ten. If they can build those faster and cheaper than the first, if they can prove the learning curve is real, then maybe, just maybe, they’ll have cracked it.

The iPhone of energy? We’ll see. Ask me again in 2035. By then, we’ll either be plugging in our electric cars to a grid powered by a fleet of British-built reactors or we’ll be explaining to our kids why we spent another decade talking about nuclear instead of building it.

I know which outcome I’m hoping for.

Sources:

https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/articles/edf-announces-hinkley-point-c-delay-and-big-rise-i

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/rolls-royce-smr-selected-to-build-small-modular-nuclear-reactors

Picture sources:

https://www.rolls-royce-smr.com/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rear_view_of_afterburner_in_sectioned_Rolls-Royce_Turbom%C3%A9ca_Adour_turbofan.jpg

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/nov/13/us-disappointed-that-rolls-royce-will-build-uks-first-small-modular-reactors

https://environmentagency.blog.gov.uk/2023/04/03/taking-the-rolls-royce-small-modular-reactor-smr-to-the-next-step/